There are no such things as natural disasters, only situations with disastrous consequences due to lack of social preparedness. This sentiment was a quite common one to encounter during my time working in emergency management. For example, Ilan Kelman states,

The term “natural disaster” is often used to refer to a disaster which involves an event originating in the environment. The term has led to connotations that the disaster is caused by nature or that these disasters are the natural state of affairs. In many belief systems, including Western thought, deities often cause “natural disasters” to punish humanity or to assert power… The argument is that natural disasters do not exist because all disasters require human input. Nature sometimes provides input through a normal and necessary environmental event, such as a flood or volcanic eruption, but human decisions have put people and property in harm’s way without adequate measures to deal with the environment. The conclusion is that those human decisions are the root causes of disasters, not the environmental phenomena. They are not “natural disasters”, but are social constructions.

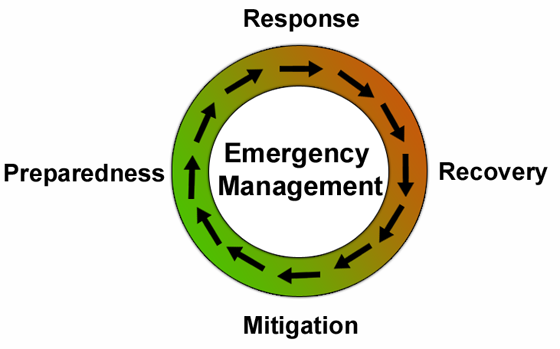

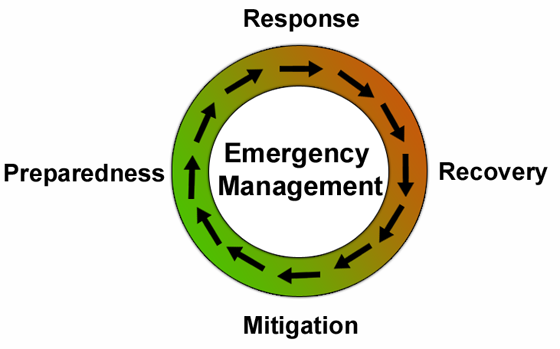

The point for many of those working in the field is that the complete fallout of most disasters can be reduced, minimized or even eliminated by proper preparedness and mitigation. The problem is that funding for emergency preparedness is usually not allocated prior to a disaster, as most governments and institutions are largely in denial about existing risks or do not have the prioritization in their funding until after a disaster occurs.  In common law, an “Act of God” or force majeure is treated as an intervening cause used to diminish liability, unless foreseeability is present. It can also be used as an impossibility or impracticability for an implied defence to frustrate a contract, unless the contract is an indemnification for the natural event in question. The Supreme Court of Canada stated in Atlantic Paper Stock Ltd. v. St. Anne-Nackawic Pulp and Paper Company Limited, [1976] 1 SCR 580,

In common law, an “Act of God” or force majeure is treated as an intervening cause used to diminish liability, unless foreseeability is present. It can also be used as an impossibility or impracticability for an implied defence to frustrate a contract, unless the contract is an indemnification for the natural event in question. The Supreme Court of Canada stated in Atlantic Paper Stock Ltd. v. St. Anne-Nackawic Pulp and Paper Company Limited, [1976] 1 SCR 580,

An act of God clause or force majeure clause… generally operates to discharge a contracting party when a supervening, sometimes supernatural, event, beyond control of either party, makes performance impossible. The common thread is that of the unexpected, something beyond reasonable human foresight and skill.

As you can probably expect, insurance companies use these force majeure provisions in their contracts. However, we are finding that given the increased complexity of modern commercial practices, these terms are becoming more difficult to interpret and apply. Insurance coverage for disasters is considered one of the best way to mitigate risk of damage or interruptions to business continuity. One of the significant fallouts of climate change is an indisputable increase in natural disasters. For insurers interested in continuing to provide legitimate coverage for unexpected or unforeseeable events, proper emergency preparedness becomes a concern with a significant price tag attached to it. A new class action lawsuit launched by Illinois Farmers Insurance Company, Farmers Insurance Exchange and their subsidiaries, against dozens of municipalities in the Chicago area over flooding which occurred in April 2013. The Chicago Tribune reports,

While the plaintiff’s attorney declined to comment on the specifics of the complaint, the lawsuit states that hundreds of claims could be included in the proposed class action.

“The common, central and fundamental issue in this action is whether the Defendants have failed to safely operate retention basins, detention basins, tributary enclosed sewers and tributary open sewers/drains for the purpose of safely conveying stormwater,” the lawsuit states.

…

Members of the potential plaintiff’s class sustained uninsured losses to their properties and possessions due to the flooding, and the insurers paid money to policy holders for property damage and “emergency restoration and remediation of sewer waste contaminated homes,” the suit states. “Farmers has taken what we believe is the necessary action to recover payments made on behalf of our customers, for damages caused by what we believe to be a completely preventable issue, as well as to prevent it from happening again,” Farmers spokesman Trent Frager said in a statement Monday. Given the number of claims, claimants and damages involved, the class action is the appropriate method for fair and efficient adjudication of the case, the lawsuit states.

According to the

Christian Monitor, the case will hinge on whether the increase in natural disasters is foreseeable, and how municipal government should manage their budgets before disasters occur,

The suit alleges the towns had “actual or constructive notice” of sewer defects based on prior incidents and investigations of those past incidents.

The potential danger of failing to properly manage stormwater and sanitary sewer systems “was foreseeable and greatly outweighed the practicability and cost of proper management of its sewers,” the lawsuit states.

The governments should have been prepared for a higher volume of rain that would fall more intensely and for a longer duration due to climate changes during the past 40 years, the lawsuit states.

The rain that fell on those two days in April 2013 was “reasonably manageable” by the towns and “was an ordinary rainfall experience” within the context of Will County’s rainfall history, according to the lawsuit. It was not an “‘Act of God’ rainfall,” the lawsuit states. “If this defendant had adopted reasonable stormwater management practices, the sewer water invasions suffered…would not have occurred,” the lawsuit alleges.

Emergency management professionals have had limited success in encouraging governments around the world to properly invest in emergency preparedness measures. Although emergency preparedness enjoyed some higher profile after 9/11, risk allocation typically follows sensational or public interest issues like terrorism rather than higher risks like flooding given the higher political capital gained from the former. A financial incentive based on liability may spurn change in governmental priorities where public interest and education campaigns have failed. However, in Canada there are significant obstacles in governmental liability for what could be construed as regulatory failures, under the Cooper v. Hobart and Edwards v. Law Society of Upper Canada analysis, as well as the subsequent Supreme Court decision in What can be done to increase governmental responsibility is additional statutory provisions creating private law duties to the public, or a greater regulatory role in advising and assisting other parties in reducing the risk and harm to the public. The proximate relationship between governmental action, in this case taking measures which could eliminate or minimize the harm done by natural events, and the members of the public suffering the harm will continue to be challenging, especially where such actions are considered discretionary. The role of insurance companies, especially in acting on behalf of the public against governmental authorities, may provide the resources and momentum to increase scrutiny over the issue of emergency preparedness. Governments expecting and anticipating these legal challenges can at the very least make their emergency preparedness plans and rationale for funding allocations more transparent and subject to public scrutiny prior to any incidents. U.K. Law Commission recommendations in 2008 over public authority liability have not been adopted there, and it is unlikely we will see any similar reforms in Canada any time soon unless these American class actions encounter considerable success.

In common law, an “Act of God” or force majeure is treated as an intervening cause used to diminish liability, unless foreseeability is present. It can also be used as an impossibility or impracticability for an implied defence to frustrate a contract, unless the contract is an indemnification for the natural event in question. The Supreme Court of Canada stated in Atlantic Paper Stock Ltd. v. St. Anne-Nackawic Pulp and Paper Company Limited, [1976] 1 SCR 580,

In common law, an “Act of God” or force majeure is treated as an intervening cause used to diminish liability, unless foreseeability is present. It can also be used as an impossibility or impracticability for an implied defence to frustrate a contract, unless the contract is an indemnification for the natural event in question. The Supreme Court of Canada stated in Atlantic Paper Stock Ltd. v. St. Anne-Nackawic Pulp and Paper Company Limited, [1976] 1 SCR 580,

Comments are closed.