What Reforms Does the Ontario Superior Court Most Need?

Tasked with proposing reforms to the Ontario Rules of Civil Procedure, the Civil Rules Working Group (“Working Group”) misfired rather badly. For example, the Working Group proposed adding a prelitigation protocol that would in effect require plaintiffs to serve their Affidavit of Documents before commencing litigation and accordingly disclose sensitive information (think medical records, bank and credit card statements, tax returns and proprietary business information) directly to opposing parties, often before such parties had retained counsel. Ignoring privacy issues and resultant risks of such information being posted online, because why not, this would add significant up front cost to all cases, including those that would otherwise settle after claim was filed but before documents were exchanged, and would seem to run counter to the Working Groups stated goals of reducing “cost and expense.”

Next, regarding expert witnesses, the Working Group both proposed to eliminate the right of parties to select their own experts in certain cases while in others adding requirements for experts, after having produced reports, to “meet and confer”, adding yet further cost.

Further, despite the acknowledged scarcity of judges (not enough Judges for the current workload) the Working Group proposed increased judicial oversight of each case (increasing the workload of existing Judges). Apparently, further judicial time will become available once the Court adopts the Working Group’s most profound, if stupid proposal, namely the elimination of oral discoveries, under the naïve assumption that henceforth, litigants would “cooperate and tell the truth.” Of course, this would require the Court to resile from its common law traditions and eliminate the ability of parties to test evidence in all but the half percent of cases that reach trial, but hey, what’s that old saying about “breaking a few eggs?”

For obvious reasons, the Working Groups’ proposals were almost universally panned (with numerous critiques posted here). One of the more muted criticisms came from the Ontario Trial Lawyers Association, who noted the Working Group admitted, apparently without appreciating the irony, that its proposals were not data driven (despite the Working Group being provided with significant data on court performance which the court had previously gone to great lengths and employed dubious legal reasoning to hide from public view). The Federation of Ontario Law Associations was less generous, calling the proposals misguided and bad for the public. The Canadian Defence Lawyers described the proposals as radical while at least one Toronto based senior partner described the proposals as “insane.” The question remains what reforms the Superior Court most needs that the Working Group should have proposed instead?

To consider that, it is worthwhile to look at the data provided to the Working Group, namely various tables on Superior Court performance, that until released to the Working Group, Canadians had no legal entitlement to access. These tables included information on the:

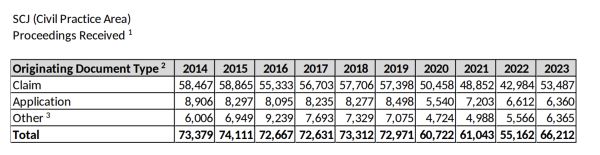

Number of Cases Commenced by Year:

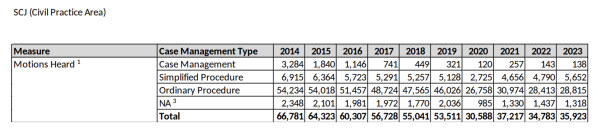

Number of Motions Heard by Year:

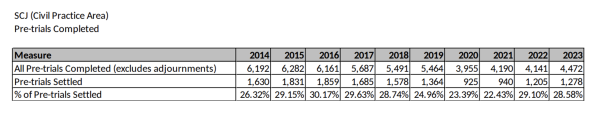

Number of Pre-Trials Completed by Year:

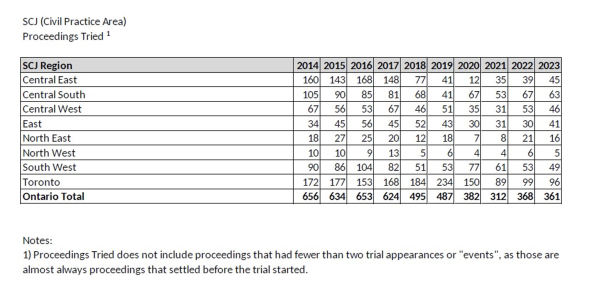

Number of Trials Per Year:

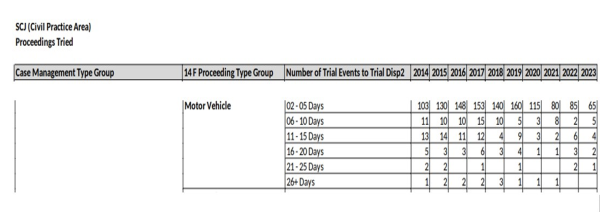

and Average Trial Length by Case Type (Motor Vehicle selected for this example):

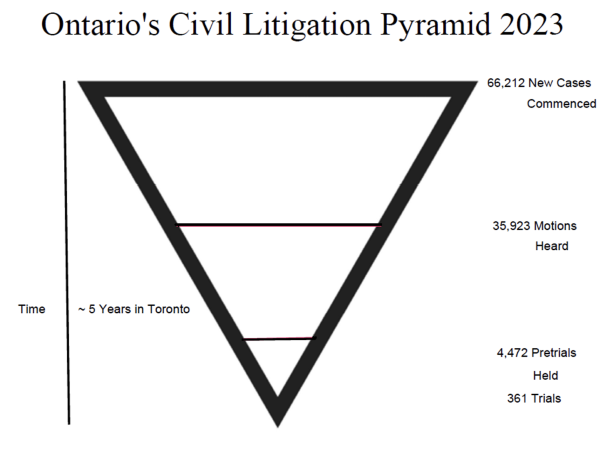

The above tables illustrate a clear trend of declining judicial performance (though this has not stopped the Judiciary from requesting a $60,000 a year raise). Specifically, while new civil claims declined by just under 10% over the ten-year period, the number of motions heard dropped by nearly half. Pre-Trials held likewise dropped by nearly 30% while the number of trials dropped by nearly 45%. Interestingly, the percentage of cases reaching trial (half of one percent) is well below the rate in New York State, which having a similar population (but higher rate of civil cases per capita), manages to hold nearly 4x more civil trials yearly. It is also important to note that the majority of matters reaching trial (close to 90%) require less than 5 days of court time.

Some of the above data can be visually represented by the ‘litigation pyramid’ shown below. Based on the best available data, at least it Toronto, it takes cases around 5 years from filing to reach trial. That is several times longer than civil cases in New York State.

Given the close integration between Ontario and the US economy, along with the fact that the current Ontario rules are essentially a less well developed version of the American Federal Rules, it makes sense to explore both those limited areas where the Ontario Superior Court outperforms its American peers along with the substantial areas where it does not. In terms of outperformance and having once practiced in the US, I have identified two specific areas. First, many US States maintain strict pleadings requirements that apply to both claims and defences. Such requirements are enforced by procedural Motions to Strike/Demurers that utilize court resources (determining whether all elements for breach of contract were plead) without advancing cases substantively. Thankfully, such unnecessary motion practice is generally absent in Ontario. Second, where default has been noted, the Ontario Superior Court permits Judgment to be entered on written motion while at least some States (Florida) require formal trials with oral evidence, again using court resources unnecessarily.

The situation reverses when it comes to discovery. Initially, the current Rules lack a sensible procedure to obtain production of relevant documents (i.e. whether the cigarette company has any documents showing it to have knowledge of the harmful effects of smoking), especially from recalcitrant defendants. Specifically, while such documents are required to be produced (R. 30.02), where such production does not voluntarily occur, the opposing party can either request production via correspondence, bring a speculative motion in advance of discoveries, to the effect that such documents must exist and hence should be produced or as is generally the case, tease out the existence of such documents at discovery, request undertakings for production, and then reattend at discovery as necessary. Depending upon the parties and counsel, one or more motions may be necessary along the way. Conversely, production is dealt with much more efficiently under the current US Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, with Rule 34 providing a mechanism to request disclosure and Rule 37 setting forth sanctions for failing to comply, up to and inclusive of the striking of pleadings. The Working Groups suggestion to deal with this via Redfern requests and interrogatories is not superior to US FRCP 34, which our courts should simply plagiarize and adopt.

Ontario’s rules in regards to oral discovery are likewise backwards and unworkable (and so byzantine that they are perhaps best ‘summarized’ over a 50 or so page summary guide). Specifically, Rule 31.06 limits examination to “any proper question.” Thus, out of court examinations take on the character of in court examinations, replete with debates, objection and refusals. Where obstruction is sufficiently egregious, this results in undertakings and refusals motions, placing further strain on limited court resources. Our courts meanwhile have developed such extensive, if worthless jurisprudence on relevance and ‘proper questions’ that opinions on routine discovery motions can run to nearly 300 paragraphs. By wordcount, that is around one third longer than the Shawshank Redemption, though the issue ultimately boils down to “should the question have been answered at discovery” or “should the document have been produced?” Unworkable rules and long-winded opinions could explain in part the declining judicial performance noted above.

The Americans have likewise adopted much more workable rules in regard to oral discovery. Stated plainly, they basically direct parties to “answer the question and we can deal with issues of propriety or admissibility at trial,” (which also tends to be the way such matters are handled for ‘friends of the court’ who are entitled to the concierge level of service provided by the commercial list in Toronto) which most of the time does not occur (as most matters settle such that determination is unnecessary). This is set forth by US FRCP 30, which both limits objections and directs that testimony is taken subject to any such objections. Were Ontario to adopt such a rule with appropriate sanction for non-compliance, it would likely vastly reduce the time and complexity of discovery motions, without the need to eliminate discoveries altogether. Further, under the longstanding American Rules, all discoveries can be visually recorded, which further reduces the incentive for parties to misbehave. Rather than scrap oral discovery entirely as the Working Group suggests, it would make more sense to simply adopt the American Rules verbatim.

While considering reforms, the Working Group should give thought as to whether Ontario really needs 3 courts of first instance (Small Claims, Superior and Divisional)? Considering Divisional Court, it sometimes acts as a trial court, sometimes as a court of appeal, and sometimes, has only partial (yet exclusive) jurisdiction (over for instance a Writ of Mandamus but not over Declaratory Relief on the same set of facts), along with the Superior Court, with both courts having the same Judges (but with the Divisional Court generally requiring matters heard by 3 judges sitting together). In the event Divisional Court is to continue, it would at least make sense to allow Superior Court judges to exercise jurisdiction in all three courts and/or to transfer matters easily between them, to cut down on the expensive development of an academic jurisprudence on transfer between 3 branches of the same court.

In Rule 48.04, Ontario has implemented an unnecessary road block to the timely resolution of cases. Specifically, to obtain a trial date, parties must file a ‘trial record’ and pay a filing fee. However, pursuant to R. 48.04, once they do so, they can no longer continue any form of discovery or bring refusals motions or motions for production of further documents (i.e. further and better affidavit of documents) absent leave (though they are permitted to bring undertakings motions arising from the same discovery). Thus, cautious counsel are incentivized to not file trial records (getting in queue for trial) until after discovery issues have been dealt with, and obtaining a motion date in Toronto often occurs a year or so into the future. If successful, time will be provided for further production and then further examinations must be scheduled, adding significant, if unnecessary delay. In the US in contrast, discovery generally occurs while matters are proceeding to trial.

Though adding nothing substantively to litigation besides cost and delay, the Working Group apparently gave little thought to reforming the Rules in a way to reduce general courthouse dysfunction, which is endemic in Ontario with each courthouse operating as its own little fief. This is perhaps best exemplified by the continued inability of various courts to accept routine documents for filing. A few recent personal examples that come to mind include rejecting a default judgment for being off by a penny (on a $550,000 judgment, due to not carrying enough decimals to satisfy the Clerk) and rejecting an Order setting aside an incorrectly entered Default on Consent as lacking a supporting motion (to the effect that the Court made a mistake given a Defence was timely filed).

However, courthouse dysfunction also manifests via differing and conflicting local practices, such as a general requirement to file documents online, yet local dictates that Judges additionally be provided with full paper copies of all documents in advance of hearing. In one of my recent cases, an in-person attendance was required half-way across the Province on a short unopposed motion, despite the prior Provincial Practice Direction that the presumptive mode of attendance in such cases was virtual. Had such hearing gone forward (Consent was obtained shortly prior to hearing such that the matter proceeded in writing), my client would have faced several thousand dollars in pointless counsel commuting costs. This dysfunction also manifests in the more mundane, such as the phones not being answered at court or emails timely responded to.

While the Working Group came up with a number of good ideas as I have previously noted, they likewise misfired in a number of areas, which is to be expected when trying to dictate top down solutions without significant input from stakeholders. Hopefully, the Working Group will consider the extensive feedback they have received and further consult, or at the very least, copy what the American have done, given the American’s much greater knowledge as to how to run a functioning court system.

Having watched this from the next province, I am curious why there seems to be so little consideration of practice and recent reforms in the rest of Canada. Québec is a decade into its new Code of Civil Procedure, which made some things better (simpler discovery) and somethings more complicated (case protocols that go back before the court every time they change): https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en/knowledge/publications/a1e47442/a-five-part-breakdown-of-quebecs-new-code-of-civil-procedure Did anyone check how it worked out in the stats?f In BC, it is common to set trial dates and do discovery working backward – I don’t know why other jurisdictions don’t try that. The addition of written motions to Federal Court procedure in 1998 was a great idea.