The Day of Destruction

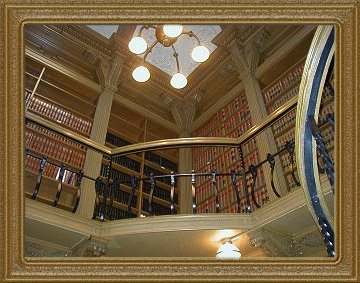

10.10 March 8, Great Library, Law Society of Upper Canada, Osgoode hall, Toronto

Slit. Rip. Toss.

The sound of buckram leather bindings being sliced from the American collection in the Great Library. Dust settling in the big bins where the paper is going off for recycling at a few dollars a ton. Workmen with exacto knives attack the old West Law Reports.

What’s happening? The Great Library is embarked on its biggest discard operation. American caselaw is going the way of all flesh. Why should libraries squeezed for space keep the books, which no-one wants? It’s all on Westlaw and Lexis anyway.

Well yes it is, and readers of Slaw won’t deny progress. But I was deeply saddened to witness the process of tearing law books apart.

I know the Great Library needs the space, and that shelf space is never infinite, but I just wonder what we have lost.

This isn’t just premature nostalgia for print or Nicholson Baker’s rant against illegible micofilm.

I wonder whether there isn’t something in the act of browsing and shelf reading that in fact turns up useful and relevant research, but will never occur in research that is subject to Boolean strictures.

I wonder whether the process of research may not be more directly shaped by whether material is there to be gatherered together in a library, as opposed to being paid for page by page.

I’ve been the frustration of every neat, reshelving librarian I’ve ever worked with because my working habits involve pulling a couple of dozen volumes of case law off the shelf, and then start to quickly scan the pages to determine which four or five are worth reading and analyzing closely. I tend to do a lot of shelf-reading and browsing through indexes and tables of contents.

Will I do that as readily – pursue footnotes or check on a Key Number reference – if I have to incur Westlaw charges, in addition to my hourly rate? Will I seek out answers that may not be obvious? Will I really go beyond quick and dirty research for all but the largest stake cases?

I can say, of course, that’s what researchers are trained to do. And yet. And yet.

Who knows what we lose when we move to purely electronic access. And the American Room, whose gorgeous Victorian design we all love, will never quite be the same again.

This is very distressing news. The American Room is one of my favourite rooms in any building anywhere, and without the beautifully ordered rows of US reports it won’t be the same. I do hope, though, that the shelves will be filled with books when the American material is gone.

Simon, you can always come out to the ‘other’ Osgoode and look at our set if you need a fix. We’ve cancelled the subscription but no plans to do away with the volumes.

recycling ? you folks are just too high tech. here in the arctic, the owner of the shack out back is taking my ‘surplus’ materials to use as kindling to stay warm for the rest of the winter. and yes, winter is back in iqaluit despite last week’s dubious ‘warmest in canada’ distinction.

hoping to move some of the remaining books into the new building as early as next week …

Trouble is paper is lousy fire fuel. In quantity just smoulders, smoke is a problem, and it generates too much ash. What else can we send you to burn?

I’m not surprised to hear this. As Nick says, most large Canadian law libraries has stopped subscribing to all but the US Sup Ct reporters, and there will in the near future be a purge of the print volumes from library shelves. This is the so called “digital dividend”. I think this change is inevitable, although regrettable, and is to be embraced rather than opposed. Simon F has it right, though, we are still in a mixed world of print and non-print, and the real question is what will replace the discarded material. Bearing in mind comments made in earlier postings on SLAW about the internationalization of Canadian law.

Simon, I would think that the Great Librarians would agree with you and are parting with these reluctantly. And I certainly agree with you about the importance of the process of research as it affects the final result. I had a conversation about this once with one of the lawyers in our litigation department. He commented that despite being something of a techno-geek himself, he has noticed that a memo written by a student who has done most of his/her research by searching keywords is quite a different beast from one that is based on a more, dare I say “traditional” canvass of the available sources via browsing, indexes, etc. He was reminded of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle in the field of physics — http://www.thebigview.com/spacetime/index.html. It’s a bit of a leap (quantum leap? – sorry) to draw an analogy to legal research, but one could say that the act of analyzing/measuring information retrieved by keywords may result in “blurring” of the measurement of the value of information retrieved from sources that are already structured.

I can attest that you tell no lie when you say that you do have a habit of pulling many volumes off the shelves at once. Far from finding it frustrating however, I like to leave the books out for a a while, as I think it reinforces, particularly for the students, that researchers do find value in canvassing the traditional sources.

Finally, since it is Friday, you may find a little entertainment in this link to Wikipedia on physicists’ humour (apparently not an oxymoron) as it relates to Heisenberg — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncertainty_principle#Humor.

I must take some exception with Laurel’s comments. I think it is an outworn adage that print research is superior to online legal research, because of the superiority of the taxonomies and indexes. That may have been the case in the early days, but now the sophistication of the online databases and computer technology make electronic research equal if not superior for legal research in almost every case.

The real issue is not the method of the research, but which method is best suited to how lawyers learn and acquire knowledge. I have never found much on this, although if someone knows of a search please let me know. What we do know from designing space for law students is that they need more physical space than other students, because they are synthesizers and spread out material around them when working. This is as Laurel suggests. CALR simply allows the researcher to find the material faster and with more accuracy, and gives them more time to analyse the results, which is the real work of a legal adviser.

The question of print arises in a close study of the history of the book. It is also clear, at least to me, that the book as a piece of information technology is simply unbeatable for sound and thorough comprehension of a subject, not just its constituent parts. For instance, if you want to know just about secret trusts, you could consult the CED; however, if you want to learn about the law of trust, then you would thoughtfully read a leading text.

It remains to be seen whether the e-book can do this as effectively as the printed book can.

I often tell students that serendipity” is a vastly underrated part of the research process. And while there is electronic serendipity as well as print serendipity I don’t think that they are quite the same. I actually think that serendipity utilizing print sources goes under the category of acquired knowledge, I’m not sure if the same rings true for research using the e sources.

Or as Umberto Eco put it at http://www.let.leidenuniv.nl/Arthis/website/mijlpalen/serendip.html

Serendipities

“I wanted to show how a number of ideas that today we consider false actually changed the world (sometimes fot the better, sometimes for the worse) and how, in the best instances, false beliefs and discoveries totally without credibility could then lead to the discovery of something true (or at least someting we consider true today). In the field of the sciences, this mechanism is known as serendipity. An exellent of it is given us by Columbus, who -believing he could reach the Indies by sailing westward- actually discovered America, which he had not intended to discover.

But the concept of serendipity can be broadened. A mistaken project does not always lead to something correct: often (and this is what happened in many projected perfect languages) a project that the author believed right seems to us unrealizable, but for this very reason we understand why something else was right. Take the case of Foigny: he invents a language that cannot work, and he invents it deliberately to parody other languages seriously proposed. But by doing so he helped us see (probably beyond his own intensions) why, on the contrary, the imperfect languages we all speak work fairly well.

Like Neil, I’m an advocate of using the source that is appropriate to the task. I did not mean to suggest the print is always better. In fact, rather than finding that indexes are better finding tools than keyword searches, I am often disappointed in the indexes to most texts. It is frustrating to suggest to a student that one start with a text when the index almost invariably does not refer to the subject at hand — therefore reinforcing the students’ desire to start with keyword searches. And of course there is the confusion between print vs. electronic and primary vs. secondary. My experience with our students is that they want to start every research project with cases (for which they use online sources), rather than with texts that are for the most part only in print.

Therefore, I cannot agree that “CALR simply allows the researcher to find the material faster and with more accuracy, and gives them more time to analyse the results, which is the real work of a legal adviser.” Very often we find that students use CALR to plow their way through tens or even hundreds of cases to try to piece together what the law is, rather than to first consult the writings of an authority on the subject. Although the former method is no doubt educational for the researcher, it can be much more time-consuming than the latter and as such, is not the client-centred approach that those of us in law firms encourage.