Grappling With the Future of CPD

Lawyers have always needed to stay current with developments and changes in our field. The proliferation of information online has changed this responsibility, and creates new challenges as well as new opportunities.

In 1998, David Blunkett, Secretary of State for Education and Employment, stated in a green paper called The Learning Age,

We are in a new age – an age of information and global competition. Familiar certainties and old ways of doing things are disappearing. The types of jobs we do have are changed as have the industries in which we work and the skills they need.

At the same time new opportunities are opening up as we see the potential of new technologies to make our lives better. We have no choice but to prepare for this new in age in which the key to success will be continuous education and development of the human mind and imagination.

Lawyers receive extensive education. It’s not uncommon in Canadian law schools that law students have a Masters degree and sometimes a PhD before gaining admission. Despite this, legal education appears to be unique in some ways.

Benjamin et al. studied the effects of legal education on the emotional well-being of law students at the University of Arizona Law School by looking at standardized self-reporting instruments such as the Brief Symptom Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory, Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist, and the Hassle Scale.

The researchers found that these law students developed normal symptom responses prior to law school, but during law school demonstrated significantly elevated levels of obsessive-compulsive behavior, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism (social alienation and isolation). These symptoms do not necessarily dissipate on graduation.

The researchers conclude,

The pattern of results suggests that certain aspects of legal education produce uncommonly elevated psychological distress levels among significant numbers of law students and recently graduated alumni.

Concern around mental health in the legal profession should ideally start in law school, and this has direct implications for practice. The authors cite A. S. Watson in Some Factors in the Contemporary Regulation of the American Legal and Medical Professions,

These assumptions are particularly troubling, because if a lawyer “is to be a wise advisor and avoid being merely a hired gun, it is necessary for him to develop emotional and intellectual freedom in order that he can perceive wise choices.”‘

Put slightly differently in 1927 by Felix Frankfurter, a Harvard Law Professor who would later sit on the Supreme Court,

In the last analysis, the law is what the lawyers are. And the law and the lawyers are what the law schools make them.

In discussing the education continuum, from law school through to the bar, Robert MacCrate stated in 1994,

I suggest that truth in education is just as important as truth in lending. Law students need to be informed consumers of legal education if they are to participate intelligently in their own professional self-development. Students and clients are essential constituencies to be taken into account. They largely foot the bills and their needs can no longer be slighted, either by law schools or by the practicing bar.

MacCrate was the author of an ABA TaskForce which focused on this topic, producing a report in 1992, Legal Education and Professional Development -An Educational Continuum. The twenty-year review after this report found that law schools had improved in their focus of including skills necessary for practice into legal education, but also highlights some of the costs and contours of legal education that can still be improved. What is obviously apparent is that the teaching continues still after becoming a lawyer,

Law schools must prepare graduates for a legal world that is not only very different from what graduates faced even a decade ago, but one that is also changing more rapidly than in the past. The constant now for all graduates, wherever they start their careers, is change.

Given the psychological impact of legal education on lawyers, many are unsurprisingly skeptical or reluctant to undertake additional studies or training. Unfortunately for them, all jurisdictions in Canada require CPD to maintain their license. The Law Society of Upper Canada explains the purpose of CPD:

Continuing professional development (CPD) is defined as the maintenance and enhancement of a lawyer’s or paralegal’s professional knowledge, skills, attitudes and professionalism throughout the individual’s career. It is a positive tool that benefits lawyers and paralegals and is an essential component of the commitment they make to the public to practise law or provide legal services competently and ethically. The Law Society has an important role to play in supporting the efforts of lawyers and paralegals to maintain and enhance that competence. It also has a duty to ensure that all persons who practise law or provide legal services in Ontario meet standards of learning, professional competence and conduct that are appropriate for the legal services they provide.

As a result, the number of parties delivering CPD programs has exploded, including as provided by the law society itself. Lawyers are compelled to be consumers of this legal education, if they like it or not. Whether the 12 required annual hours in Ontario, and 3 “professionalism” hours, are sufficient to maintain competence is a different question.

Christopher Roper highlights several distinctions between legal education and continuing legal education, including the need for flexibility and application. But he also laments the lack of a conceptual framework or use of pedagogical theory, which could make it more professional.

CPD is something studied by educators outside of the legal field, and the efficacy of different programs varies. Collin et al. note that literature on workplace learning emphasize that successful CPD requires both individual motivation and the learning needs of participants. Although CPD is invariably undertaken as an individual, its effectiveness is accentuated by an active learning climate which allows participants to ask questions, seek feedback, reflect on potential results, explore and experiment.

What CPD needs is an application to practice. Etienne St-Jean examined 360 entrepreneurs participating in a mentorship arrangement, testing the model below, and found that career supports played the most significant role in professional development.

These supports presented as integration of the mentee into the target community, for example, by introducing them to others who they know. The informational support creates idiosyncratic learning through peer exchange.

New information can help these entrepreneurs identify new business opportunities. Reflective practice is facilitated by confronting the mentee about ideas, especially where beliefs habits and attitudes act as an obstacle, in order to foster problem-solving.

The psychological functions and relationship also play a role in this learning, especially in allowing open disclosure between the parties to improve candidness in the problem-solving framework. Leslie C. Levin states in Preliminary Reflections on the Professional Development Of Solo and Small Law Firm Practitioners,

Any attempt to understand the professional development of solo and small firm lawyers must consider the social settings in which they practice. A lawyer’s training and professional socialization can be deeply affected by the other attorneys with whom the lawyer works and the people from whom she seeks assistance.

The heavy emphasis on relationships here means that CPD alone may not create the outcomes desired by law societies, and may also require facilitation by other members of the bar. When you take an already busy practitioner and need another practitioner to coordinate, the scheduling can become a nightmare.

One of the potential solutions is to use emerging technology to create these relationships virtually. The new Law Practice Program delivers the vast majority of its content online. The Ontario Bar Association, who hosts one of the largest CPD events annually at its Institute, is also moving online. Osgoode Professional Development already has sophisticated teleconference and recording capabilities. Even LSUC has moved to delivering its Professional Responsibility and Practice (PRP) Course, mandatory for students in the articling program, through an independent modular format.

Not all online CPD are built the same though. Most of these offerings are usually archived webinars that were dated and of poor quality. A newer entry on the scene seeks to change this.

Grapple Law was launched in October 2014, using HD studio content and utilizing best e-learning practices. They also create on-demand content for more focused needs. The site is the lovechild of Rohit Parekh, Director of Innovation at Conduit Law Professional Corporation, and his brother, Rahul Parekh of Tiffin Media, a new media production and consulting firm.

The site tracks your CPD use and helps you calculate how many hours you still need. The developers are steadily building content and plan on expanding to other jurisdictions.

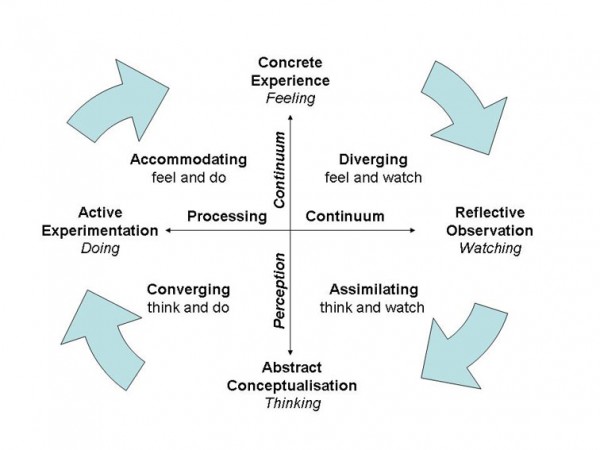

Friedman et al. developed evaluation criteria for online CPD from experiential learning cycle theory through a quick survey of 300 online courses and an in-depth analysis of 5 of these.

The suggestions they provide include a mechanism to record detailed goals, plans and feedback within a framework to plan and assess their learning. These online courses should be structured in a logical sequence and direct users to additional information as needed.

They found that online CPD may best be geared to the third conclusion stage (3. Abstract Conceptulization) of the experiential learning cycle, which focuses on the following:

- Evaluation of what has been learnt

- Relevance to day-to-day work

- Opportunity to share models and concepts with others and re-evaluate

- Accreditation of activity and learning

For the other three stages, experience (1. Concrete Experience), reflection (2. Reflective Observation), and planning/action (4. Active Experimentation), a blended format using offline supports may be more useful, but only where the participants are still at the novice stage or early in their professional careers.

The costs of in-person training of professional development, and the increased need for flexible delivery, ensures that we will have more online CPD offerings available. Grapple Law demonstrates what can be possible, in terms of quality and polish.

The needs of CPD users, however, will vary based on skill sets and learning styles, and will require some level of individualization for its users. This is the new age in which we will develop the minds and imaginations of the next generation of lawyers.

Comments are closed.